Introducing the section 'Language'

Of course ‘English’ wasn’t overwhelmingly dominant in Zamenhof’s day the way it is now. There hadn’t yet been two world wars which helped create a USA-centred world order. Nowadays, if you are ambitious but don’t speak American English, you are obliged to try and master it – even if you may still somehow feel ‘second class’ afterwards. British and other non-American English speakers also need to be familiar with the words and expressions of US English as it is today the world’s leading version.

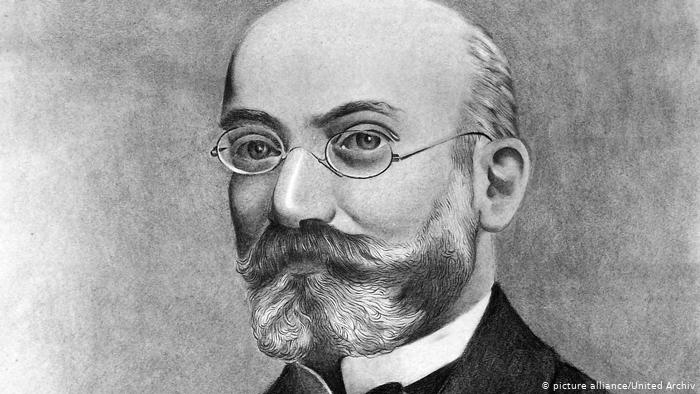

This section ‘Language’ offers some technical information and pointers to further sources on this theme. Esperanto remains ‘a small, relatively unknown enterprise’. Yet there are people who speak it in many countries and in all continents. No one knows exactly how many. A number of people grow up speaking Esperanto as one of their first languages in an multilingual family which includes it. A person who speaks or supports Esperanto is often called an “Esperantist“, but some prefer to be called simply an ‘Esperanto speaker or an Esperanto user‘. It is not a cult, but a cultural ambition to bring about a fairer world, open to all.